Introduction

The performance of any plastic shredding system ultimately depends on one critical component: the cutting blade. While motors provide power and frames provide structure, the blade geometry determines how efficiently plastic materials are reduced to the desired size. Understanding the intricate relationship between blade design, cutting mechanics, and material properties separates mediocre shredding operations from highly efficient, cost-effective systems.

This technical examination explores the engineering principles behind blade design, the physics of cutting different plastic materials, and the practical considerations that influence blade selection and maintenance strategies in industrial recycling operations.

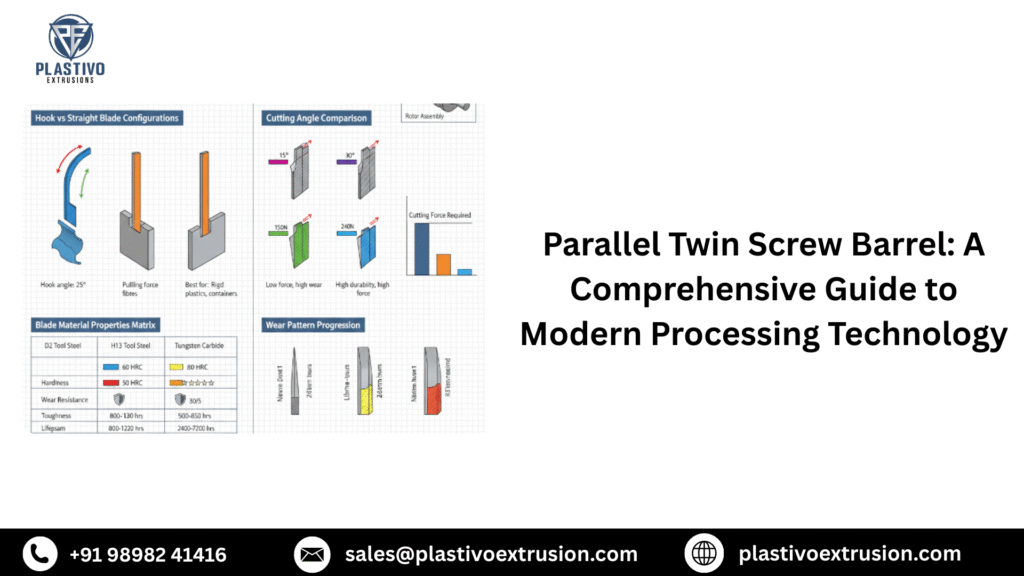

Hook Blade vs. Straight Blade Configurations

The fundamental decision in blade design starts with choosing between hook and straight blade configurations. Each geometry creates distinctly different cutting actions that suit specific applications and material types.

Hook blades feature a curved or hooked profile that creates a scissors-like cutting action as the blade passes the material. This geometry excels at grabbing and pulling material into the cutting zone, making it particularly effective for film materials, fiber-reinforced plastics, and materials that tend to slip away from straight cutting edges. The hook angle, typically ranging from 15 to 35 degrees from vertical, determines how aggressively the blade captures material.

The curved profile generates both a cutting force and a pulling force simultaneously. As the blade rotates, the hook engages the material first at the tip, then progressively cuts along the entire edge length. This action distributes cutting forces over time rather than applying them instantaneously, reducing peak power demands and creating smoother operation with less vibration.

Straight blades present a flat cutting edge perpendicular to the direction of rotation. This configuration delivers pure shearing action without the pulling component found in hook blades. Straight blade geometry proves superior for rigid plastics like PET bottles, HDPE containers, and thick-walled parts where the material maintains its position during cutting rather than deflecting away.

The absence of a hook allows straight blades to maintain more consistent edge geometry during sharpening and reconditioning. Manufacturing tolerances are easier to achieve, and replacement costs typically run 15 to 25 percent lower than equivalent hook blade designs. However, throughput may decrease with certain flexible materials that require the grabbing action of hooked profiles.

Cutting Angle Optimization

The cutting angle—measured between the blade face and the material being cut—represents one of the most critical geometric parameters affecting shredding performance. This angle directly influences cutting force requirements, edge durability, and the quality of the resulting cut.

A shallow cutting angle of 15 degrees creates an extremely sharp blade that requires minimal force to penetrate material. This geometry works exceptionally well for soft plastics, films, and materials where clean cuts without significant deformation are desired. The trade-off comes in reduced edge strength; shallow angles wear more quickly and are prone to chipping when encountering hard contaminants or reinforced materials.

The forces involved follow predictable patterns. Cutting force decreases proportionally as the angle becomes more acute, following the relationship F = k × t / tan(α), where F represents cutting force, k is a material constant, t is material thickness, and α is the cutting angle. A 15-degree angle might require 40 percent less force than a 45-degree configuration for the same material.

Medium cutting angles around 30 degrees represent the most common compromise in industrial shredding applications. This geometry balances reasonable cutting forces with adequate edge strength for extended operational periods. Most general-purpose shredders processing mixed plastic waste employ 30-degree blade angles as a starting point, then adjust based on specific material characteristics and performance requirements.

Steep cutting angles of 45 degrees prioritize edge durability over cutting efficiency. The robust edge geometry withstands impact from hard contaminants—metal fasteners, stones, wood fragments—that frequently appear in post-consumer plastic streams. While cutting forces increase substantially, the extended blade life and reduced downtime from edge damage often justify the additional power consumption.

Material properties significantly influence optimal cutting angle selection. Ductile materials like LDPE and PP deform rather than fracture, requiring sharper angles to achieve clean cuts without excessive stretching. Brittle materials such as PS and rigid PVC fracture readily, allowing steeper angles without compromising cut quality. Fiber-reinforced plastics present the greatest challenge, demanding careful angle selection to cut both the matrix material and reinforcing fibers without excessive delamination.

Blade Material Selection

The metallurgical composition of shredder blades determines their operational lifespan, maintenance requirements, and total cost of ownership. Three primary material families dominate industrial applications, each offering distinct advantages for specific operating conditions.

D2 tool steel represents the most common blade material in plastic shredding applications. This air-hardening steel contains approximately 12 percent chromium and 1.5 percent carbon, providing excellent wear resistance when properly heat-treated to hardness levels between 58 and 62 HRC. The high chromium content offers moderate corrosion resistance, important when processing washed materials or operating in humid environments.

D2’s wear resistance comes from numerous hard chromium carbides distributed throughout the martensitic matrix. These carbides, significantly harder than the surrounding steel, resist abrasive wear from fillers, reinforcing fibers, and contaminants. A properly heat-treated D2 blade processing general mixed plastics typically achieves 800 to 1,200 operational hours before requiring sharpening.

The material costs roughly 40 to 60 percent less than premium alternatives while delivering adequate performance for many applications. Heat treatment quality critically affects performance; improper processing can leave the blade too soft for wear resistance or too hard and brittle, prone to chipping. Reputable blade manufacturers employ precise heat treatment protocols with documented hardness verification.

H13 tool steel offers superior toughness compared to D2, making it the preferred choice for heavy-duty applications involving thick-walled parts, hard contaminants, or high-impact cutting conditions. This hot-work steel contains approximately 5 percent chromium, 1.5 percent molybdenum, and 1 percent vanadium, heat-treated to hardness levels of 48 to 52 HRC—softer than D2 but with significantly higher impact resistance.

The reduced hardness means H13 blades wear more quickly in highly abrasive applications, typically lasting 60 to 70 percent as long as D2 under identical conditions. However, the enhanced toughness virtually eliminates catastrophic blade failures from chipping or fracture. Operations that experience frequent blade damage from contaminants often find that H13’s reliability outweighs its faster wear rate.

H13 also performs exceptionally well in applications generating significant frictional heating during cutting. The material maintains its properties at elevated temperatures better than D2, reducing concerns about edge softening during continuous high-speed operation. This characteristic proves valuable in high-throughput shredders processing dense materials that generate substantial heat.

Tungsten carbide represents the premium option for extreme wear applications. This material class includes both solid carbide blades and carbide-tipped designs where carbide cutting edges are brazed or mechanically attached to tough steel bodies. Hardness values range from 70 to 92 HRA (Rockwell A scale), far exceeding conventional tool steels.

Carbide blades typically last three to six times longer than D2 steel in highly abrasive applications involving glass-filled plastics, mineral-filled compounds, or contaminated post-consumer waste streams. The dramatic wear resistance comes from tungsten carbide particles held in a cobalt matrix, creating a material that resists abrasion from even the hardest contaminants.

The primary limitation is brittleness. Tungsten carbide cannot withstand the impact forces that tool steels handle routinely. A carbide blade encountering a large metal contaminant or jamming against a hard obstruction may fracture catastrophically rather than merely chipping. Cost also presents a significant barrier—carbide blades cost three to five times more than equivalent D2 designs initially.

Economic analysis often favors carbide for continuous high-volume operations where blade changes create expensive downtime. A facility processing 50 tons of plastic daily might justify carbide’s premium cost through reduced changeout frequency and increased productivity. Smaller operations with periodic maintenance windows typically find D2 or H13 more cost-effective.

Shear Cutting vs. Impact Cutting Mechanisms

The fundamental mechanics of how blades interact with plastic materials divides into two distinct categories: shear cutting and impact cutting. Understanding these mechanisms allows proper matching of shredder design to material characteristics.

Shear cutting occurs when blades pass closely by each other or by stationary counter-knives, creating a scissors-like action. The clearance between moving and stationary blades typically ranges from 0.2 to 0.8 millimeters, depending on material thickness and properties. As the rotor blade passes the stationary blade, material trapped between them experiences pure shear stress.

This cutting mechanism requires precise blade positioning and tight tolerances. The clearance must remain small enough to prevent material from escaping without being cut, yet large enough to avoid metal-to-metal contact that accelerates wear. Shear cutting generates minimal noise, produces uniform particle sizes, and requires relatively low power per kilogram of material processed.

The cutting forces in shear systems follow predictable patterns based on material properties. Ductile materials require more force as they deform plastically before separating. Brittle materials fracture more readily once critical stress levels are reached. The blade edge angle affects how quickly stress concentrates at the cutting point, with sharper angles localizing stress more effectively.

Impact cutting relies on kinetic energy from rapidly moving blades striking material against stationary surfaces or other blades. No precise clearances are maintained; instead, the blade impacts the material with sufficient force to fracture it. Rotor speeds in impact cutting systems typically range from 500 to 1,500 RPM, compared to 50 to 150 RPM for shear cutting systems.

The physics differs fundamentally from shear cutting. Material fractures when the stress wave from blade impact exceeds its structural strength. Particle size becomes less uniform because fracture propagates along paths of least resistance—stress concentrations, material inhomogeneities, or pre-existing flaws. The resulting output shows greater size variation than shear cutting produces.

Impact cutting excels for brittle materials that fracture readily. Rigid PVC, polystyrene, and glass-filled composites shatter effectively under impact forces. Power requirements per kilogram can actually decrease compared to shear cutting because the material’s brittleness is exploited rather than working against it. Noise levels increase substantially due to the high-velocity impacts.

Most industrial shredders employ hybrid approaches combining both mechanisms. Primary size reduction often uses impact cutting to quickly break large items into manageable pieces. Secondary processing then employs shear cutting to achieve more uniform final particle sizes. This staged approach optimizes energy efficiency while maintaining output quality specifications.

Blade Spacing and Rotor Diameter Calculations

The geometric relationship between blade spacing and rotor diameter fundamentally determines particle size distribution, throughput capacity, and power consumption. These parameters require careful calculation during shredder design and can be adjusted during operation through blade configuration changes.

Blade spacing refers to the axial distance along the rotor between adjacent blades. Closer spacing creates more cutting opportunities per revolution, generally producing smaller particles and higher throughput. However, excessive blade density increases power requirements, generates more heat, and accelerates wear by forcing each blade to cut more frequently.

The theoretical maximum particle size approximates the blade spacing for shear cutting systems. A rotor with 50-millimeter blade spacing cannot produce particles larger than this dimension in the axial direction, though actual particle sizes typically range between 60 and 80 percent of blade spacing due to fracture patterns and material behavior.

Optimal blade spacing depends on desired output specifications and material characteristics. Film materials benefit from closer spacing—25 to 40 millimeters—to ensure adequate cutting frequency for the flexible material. Rigid parts tolerate wider spacing—50 to 100 millimeters—because larger pieces remain functional for downstream processing. Economic considerations favor wider spacing to reduce blade costs and maintenance frequency.

Rotor diameter affects peripheral velocity, which directly influences cutting forces and energy transfer. The relationship follows v = π × D × N / 60, where v is peripheral velocity in meters per second, D is rotor diameter in meters, and N is rotational speed in RPM. A 400-millimeter diameter rotor spinning at 100 RPM generates peripheral velocity of approximately 2.1 meters per second.

Larger diameter rotors generate higher peripheral velocities at equivalent rotational speeds, increasing the kinetic energy available for cutting. This allows processing harder materials or achieving higher throughput rates. However, larger diameters also increase manufacturing costs, require more robust bearing systems, and consume more space.

The number of blades mounted on a rotor involves balancing competing factors. More blades increase cutting opportunities and throughput potential but also multiply power requirements and blade costs. A typical calculation starts with desired throughput, material bulk density, and available motor power, then optimizes blade count to achieve targets within power constraints.

Practical designs commonly employ 6 to 20 blades on single-shaft rotors and 4 to 12 blades per shaft on dual-shaft systems. The blades are often staggered—mounted at different angular positions—to distribute cutting forces temporally rather than having all blades in the same rotational position. This staggered arrangement reduces peak power demands and creates smoother operation.

Wear Patterns and Predictive Replacement Strategies

Blade wear follows predictable patterns influenced by material properties, operating conditions, and blade geometry. Understanding these patterns enables transitioning from reactive blade replacement—waiting until performance degrades unacceptably—to predictive strategies that optimize operational efficiency and costs.

Abrasive wear represents the most common degradation mechanism in plastic shredding applications. Hard particles—mineral fillers, glass fibers, metal contaminants, residual sand or dirt—act like microscopic cutting tools removing blade material through mechanical abrasion. This wear appears as gradual edge rounding and material loss along the cutting edge.

The wear rate follows Archard’s equation: V = K × F × s / H, where V is volume of material removed, K is a dimensionless wear coefficient dependent on materials and lubrication, F is normal force, s is sliding distance, and H is material hardness. Harder blade materials (higher H values) inherently resist abrasive wear better, explaining why carbide outperforms tool steel in highly abrasive applications.

Visual inspection reveals abrasive wear progression. Fresh blades display sharp, crisp edges with defined angles. As wear accumulates, edges become rounded with visible material loss. Advanced wear creates a distinct “land”—a flat worn surface—along the cutting edge where the sharp edge once existed. Once this land width exceeds 0.5 to 1.0 millimeters, cutting efficiency degrades noticeably.

Impact damage manifests as chips, cracks, or fractures in the blade edge. This wear mechanism results from encountering hard contaminants that generate forces exceeding the blade material’s fracture strength. A blade striking a large bolt, rock, or metal fitting may lose a chunk of edge material instantaneously rather than wearing gradually.

Impact damage is material-dependent in predictable ways. Harder blade materials like D2 at 62 HRC or tungsten carbide become increasingly brittle and prone to chipping. Tougher materials like H13 at 50 HRC resist impact damage through plastic deformation rather than fracture. Operations frequently encountering contaminants benefit from sacrificing some wear resistance for improved toughness.

Thermal degradation occurs when frictional heating during cutting exceeds the blade material’s tempering temperature. Tool steels lose hardness when heated above certain thresholds—typically 200 to 300 degrees Celsius depending on material and heat treatment. Once softened, the edge wears rapidly even under normal cutting conditions.

This wear mechanism appears as localized softening and accelerated wear at cutting edges where frictional heating concentrates. The blade may retain acceptable hardness away from edges while the critical cutting zone becomes too soft for effective service. Preventing thermal degradation requires adequate cooling—either through lower cutting speeds, improved ventilation, or active cooling systems.

Predictive replacement strategies integrate multiple monitoring approaches. Power consumption tracking provides early warning of edge degradation; dull blades require 20 to 40 percent more power to process the same material at equivalent throughput. A gradual power increase over days or weeks signals progressive wear, while sudden increases may indicate impact damage or other acute problems.

Particle size analysis reveals blade condition through output quality. As blades dull, average particle size increases and size distribution broadens. Automated systems can monitor output continuously, triggering maintenance alerts when statistical analysis indicates degradation beyond acceptable limits. This approach prevents quality issues from reaching customers while maximizing blade utilization.

Scheduled inspection programs balance thoroughness against operational disruption. Weekly visual inspections identify obvious damage requiring immediate attention. Monthly detailed inspections include dimensional measurements of blade height, edge angles, and land width using specialized gauges. These measurements establish wear rate trends enabling accurate replacement scheduling.

Advanced facilities employ condition monitoring technologies. Vibration sensors detect changes in cutting dynamics that correlate with blade wear or damage. Acoustic monitoring identifies the distinct sound signatures of dull or damaged blades. These technologies enable transitioning to true predictive maintenance where replacements occur based on actual condition rather than calendar schedules or arbitrary hour counts.

Regrinding vs. Replacement Economics

The decision between regrinding worn blades and installing new replacements involves complex economic analysis balancing direct costs, operational performance, and practical constraints. Neither approach universally dominates; optimal strategies vary with blade material, wear patterns, operational scale, and specific cost structures.

Regrinding removes worn material through precision grinding, restoring sharp edges and proper geometry. Professional regrinding services typically charge 25 to 40 percent of new blade cost for standard tool steel blades. Multiple regrind cycles are possible—high-quality blades often withstand three to five regrinds before dimensional changes prevent further reconditioning.

The primary economic advantage is obvious: extending blade life by 300 to 500 percent while spending only 25 to 40 percent per regrind dramatically reduces per-hour blade costs. A D2 blade costing 200 dollars initially, lasting 1,000 hours, then regrindable three times at 60 dollars per regrind, delivers 4,000 total hours at a cost of 380 dollars—0.095 dollars per hour compared to 0.200 dollars per hour for replacement-only strategies.

However, multiple factors complicate this simple analysis. Regrinding reduces blade dimensions—height, width, or both depending on the regrinding approach. Eventually, geometric changes become significant enough that blade performance degrades or the blade no longer fits properly in the rotor assembly. Each regrind also removes the hardened surface layer, potentially exposing softer core material if the hardening depth proves inadequate.

Quality control during regrinding critically affects outcomes. Improper grinding generates excessive heat that softens the blade, removes too much material, or creates incorrect edge geometries. Reputable grinding services employ CNC equipment with precise temperature control and verification procedures ensuring consistent results. Cheap regrinding often proves counterproductive, returning blades that wear faster than properly serviced ones.

Transportation logistics impact regrinding economics. Facilities must maintain blade inventory sufficient to operate while blades undergo regrinding—typically one to two weeks turnaround. The inventory carrying cost and logistical complexity must factor into economic analysis. Facilities operating multiple shredders may find this easier to manage than single-machine operations where blade exchange requires operational shutdown.

Replacement strategies appeal to operations prioritizing simplicity and maximum performance. New blades deliver optimal geometry, full material dimensions, and maximum hardness throughout their depth. Performance remains consistent across the blade’s service life without the gradual degradation sometimes experienced with multiple regrind cycles.

The premium paid for replacement purchases operational convenience. No inventory of spare blades awaiting return from regrinding services. No quality variation between new and reground blades. Simplified logistics with predictable costs per blade change. These factors particularly benefit smaller operations lacking dedicated maintenance departments or those operating in remote locations where regrinding services prove difficult to access.

A hybrid approach often proves optimal. Initial service life runs until moderate wear accumulates, then the blade undergoes one or two professional regrinds. After exhausting practical regrinding opportunities, the blade is retired and replaced. This strategy captures most of regrinding’s economic benefits while avoiding the complications of excessive regrinding cycles.

Carbide blades require different analysis. Regrinding tungsten carbide demands specialized diamond grinding equipment; costs typically reach 60 to 80 percent of new blade prices. Combined with carbide’s extended service life, the economics often favor replacement rather than reconditioning. However, carbide-tipped blades—where carbide inserts attach to steel bodies—may justify replacement of worn carbide tips while retaining the steel substrate.

Blade Hardness Requirements

Surface hardness specifications for shredder blades reflect the fundamental trade-off between wear resistance and toughness. Higher hardness provides superior wear resistance but increases brittleness and fracture susceptibility. Optimal hardness selection depends on material characteristics, contamination levels, and operational priorities.

The Rockwell C hardness scale (HRC) provides the standard measurement method for tool steel blades. This test uses a diamond cone indenter pressed into the blade surface under controlled load; the depth of penetration inversely correlates with hardness. Measurements typically occur at multiple locations along the blade to verify consistency.

The target hardness range for D2 tool steel blades spans 58 to 62 HRC, with 60 HRC representing the most common specification. This range balances excellent wear resistance from the high hardness with acceptable toughness to resist chipping from impact. Material below 58 HRC wears too quickly in most applications, requiring frequent replacement. Material above 62 HRC becomes increasingly brittle and prone to chipping.

Hardness uniformity matters as much as the absolute value. A blade with some areas at 58 HRC and others at 62 HRC performs inconsistently; softer regions wear disproportionately fast while harder regions risk chipping. Quality heat treatment produces hardness variation no greater than ±1 to 2 HRC across the entire blade, ensuring consistent performance.

Case depth—how deep the hardened layer extends below the surface—critically affects blade longevity, especially for blades subject to regrinding. Shallow case hardening might achieve 62 HRC at the surface but transition to softer material within 2 to 3 millimeters depth. The first regrind removes this hard surface, exposing softer material that wears rapidly.

Through-hardening, where the blade maintains consistent hardness throughout its cross-section, supports multiple regrinding cycles without performance degradation. Material specifications should require hardness consistency from surface to at least 6 to 8 millimeters depth—sufficient to accommodate three to four regrind cycles removing 1.5 to 2 millimeters per service.

H13 blades target lower hardness—typically 48 to 52 HRC—prioritizing toughness over maximum wear resistance. This specification suits applications where impact from contaminants creates frequent blade damage at higher hardness levels. The softer material deforms rather than fractures when overloaded, allowing continued operation despite impact events that would shatter harder blades.

Hardness testing procedures should follow standardized methods to ensure reliable, comparable results. ASTM E18 defines proper Rockwell testing protocols including surface preparation, indenter specifications, load application, and measurement procedures. Documented testing from blade suppliers provides quality assurance, though independent verification of critical batches offers additional security.

Field hardness testing using portable instruments enables in-service blade evaluation. These devices help identify prematurely worn blades that may have inadequate hardness from manufacturing defects or improper heat treatment. Regular testing of incoming blades catches quality issues before installation, preventing premature failures and associated downtime.

Temperature affects hardness measurements; testing should occur at room temperature with thermally stabilized samples. A blade still warm from recent operation provides artificially low readings. Similarly, surface condition influences results—rough, pitted, or heavily worn surfaces prevent accurate measurement. Proper testing requires clean, smooth surfaces representative of the blade’s actual condition.

Conclusion

Blade geometry and cutting mechanics represent the foundation of effective plastic shredding operations. The engineering principles governing blade design—from basic configuration choices between hook and straight profiles through detailed optimization of cutting angles, material selection, and hardness specifications—directly determine operational success.

Understanding these technical factors enables informed decision-making throughout the equipment lifecycle. Initial equipment specifications can match blade designs to specific material characteristics and operating conditions. Operational monitoring can identify wear patterns and performance degradation early. Maintenance strategies can optimize blade utilization while controlling costs through appropriate balancing of regrinding and replacement.

The complexity of blade technology continues advancing. New materials offer improved combinations of hardness and toughness. Advanced coatings extend surface wear resistance without compromising substrate toughness. Computational modeling enables optimizing blade geometries for specific applications before manufacturing physical prototypes.

Yet fundamental principles remain constant. Sharp blades cutting at appropriate angles through proper mechanical action will always outperform dull blades at incorrect angles using unsuitable cutting mechanisms. Mastering these fundamentals ensures that plastic shredding operations achieve their full potential in efficiency, reliability, and economic performance.